From Ambassador (The Draining Lake)

2021/7/13

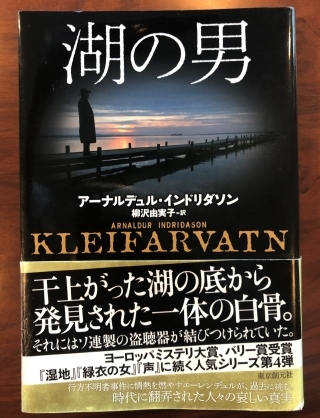

It is a mystery novel written in 2004 by Mr.Arnaldur Indridason, one of the Iceland’s most beloved authors. The book was translated into Japanese by Ms.Yumiko Yanagisawa, a translator living in Sweden, and published in Japan in 2017 by Tokyo Sogensha. Before I arrived in Iceland as Ambassador, this book was recommended to me and I was fortunate enough to have a chance to read it.

The original title, Kleifarvatn, (“The Man in the lake, Mizuumi no otoko” Japanese title) is the name of a real lake outside of Reykjavik. The story begins when a woman discovers a skeleton corpse at the bottom of the lake, which has suddenly dried up due to tectonic activity.

I especially love this introduction of the book to the extent that I have read this part several times. The woman who finds the body has nothing to do with the rest of the story, but for some reason I find the character of this lonely woman fascinating. In fact, she reappears at the end of the story and her name is revealed to be "Sunna". She is a researcher, and a water specialist at the Ministry for Energy Affairs.

It may sound a bit far-fetched to bring this up here, but it seems to me that it is an illustration of the importance of water resource management to Iceland's energy planning. The figures show that hydropower accounts for 70% of Iceland's electricity supply, and the importance of this is clear.

And for that matter, there is not a single thermal or nuclear power station in Iceland. The country's electricity comes almost entirely from hydroelectric and geothermal sources. I will put geothermal power as a subject for another article, so I shall concentrate on hydroelectric power.

I recently had the opportunity to speak to Mr.Hordur Arnason, CEO at Landsvirkjun, the company responsible for 70% of Iceland's electricity supply. He also stressed the need to make better use of Iceland's abundant water resources. Mr. Hordur believes that dams for power generation can be used for as long as 70 or 80 years if they are well maintained. The problem, he said, is that climate change and tectonic movements could make it difficult to use water resources. If the drying up of Lake Kleifarvatn, which actually happened in the early 2000s, had happened in Japan, it would have been under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport or at best, the Fisheries Agency. While in Iceland it is a matter for the water specialists in the Ministry for Energy Affairs, which is responsible for energy planning.

Mr. Hordur pointed out a possible future scenario: the sudden collapse of glaciers due to global warming, and the risk of some dams collapsing due to massive flooding...

I don't want this to actually happen, but it was a reminder for me of the huge impact it has on this country.

The original title, Kleifarvatn, (“The Man in the lake, Mizuumi no otoko” Japanese title) is the name of a real lake outside of Reykjavik. The story begins when a woman discovers a skeleton corpse at the bottom of the lake, which has suddenly dried up due to tectonic activity.

I especially love this introduction of the book to the extent that I have read this part several times. The woman who finds the body has nothing to do with the rest of the story, but for some reason I find the character of this lonely woman fascinating. In fact, she reappears at the end of the story and her name is revealed to be "Sunna". She is a researcher, and a water specialist at the Ministry for Energy Affairs.

It may sound a bit far-fetched to bring this up here, but it seems to me that it is an illustration of the importance of water resource management to Iceland's energy planning. The figures show that hydropower accounts for 70% of Iceland's electricity supply, and the importance of this is clear.

And for that matter, there is not a single thermal or nuclear power station in Iceland. The country's electricity comes almost entirely from hydroelectric and geothermal sources. I will put geothermal power as a subject for another article, so I shall concentrate on hydroelectric power.

I recently had the opportunity to speak to Mr.Hordur Arnason, CEO at Landsvirkjun, the company responsible for 70% of Iceland's electricity supply. He also stressed the need to make better use of Iceland's abundant water resources. Mr. Hordur believes that dams for power generation can be used for as long as 70 or 80 years if they are well maintained. The problem, he said, is that climate change and tectonic movements could make it difficult to use water resources. If the drying up of Lake Kleifarvatn, which actually happened in the early 2000s, had happened in Japan, it would have been under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport or at best, the Fisheries Agency. While in Iceland it is a matter for the water specialists in the Ministry for Energy Affairs, which is responsible for energy planning.

Mr. Hordur pointed out a possible future scenario: the sudden collapse of glaciers due to global warming, and the risk of some dams collapsing due to massive flooding...

I don't want this to actually happen, but it was a reminder for me of the huge impact it has on this country.